If you come visit my stand at the farmers market, you may notice that some of my veggies are on the petite side. That’s because I use my “little pumpkin” philosophy all throughout the garden. My celery is small. So are my eggplants, beets, cabbages, and a bunch of other vegetables. Sometimes it’s because I grow small varieties and plant things close together so I can fit a lot of vegetables in a small space, but oftentimes it’s because I don’t use fertilizer and extra water on the plants. I believe the result is nutrient-dense and flavorful (and not watery) food. Sometimes bigger isn’t always better…sometimes good things come in small packages.

On Being an Eater

The Dirt on Onions

Yesterday evening I decided it was time to harvest my patch of storage onions, so I hunkered down and spent about an hour and a half harvesting the onions and another hour and a half carefully laying them out to cure in the greenhouse. The time had long come when I needed to harvest the onions, and with an abundance of rain lately, I was worried about the onions rotting in the field and weeds completely taking over the patch, making it much more difficult to find the onions come harvest time. So with a dry afternoon on hand, I knew it was time to dig in.

This year, I planted two 150-ft beds of onions. Each bed was 4 feet wide and contained 2 or 3 rows of onions. One bed was devoted to “fresh eating” onions, as I like to call them, and the other was set aside for storage onions. The fresh eating onions were onions that I harvested with green tops. They don’t have any of the papery wrappers that you’re used to seeing when you buy a net bag of onions at the store. Instead, they are intended to be eaten fresh, no peeling necessary, and therefore, these onions won’t store long. Generally, they are varieties that are sweeter, containing more sugars, which contributes to their inability to store for a long time, but also makes them delicious raw and helps them to caramelize beautifully. In the fresh eating onion bed, I also included my summer leeks, which take fewer days to reach maturity than fall leek varieties, and are planted closer together so they remain small and slender, never getting bigger than a thumb’s width.

My storage onion bed contains five varieties of onions, all of which store well, according to my seed catalogs. Storage onions tend to be more pungent and less sugary, they make lots of layers of papery wrappers, and they can be cured then stored for months. Some storage onions can even make it through the entire winter if stored properly. The telltale sign that the onions are ready to harvest is when their green tops begin to brown and flop over. The onion is effectively curing itself by sealing off the watery sugars and starches in the bulb by creating a little pinched off crook in its neck where the tops fall over. This way, the green tops won’t transpire water out from the onion bulb.

Most of my storage onions had their tops flop over a couple weeks ago, but a few stalwart onions continued to have perky leaves. I picked all of the onions that had flopped and shriveled tops and laid them out in my greenhouse to continue drying for the next week or so. In the greenhouse, they will be protected from rain and receive plenty of heat to ensure their papery wrappers are good and dry for storage. The onions that continued to have perky green tops were all from one variety, Rossa di Milano, a beautiful Italian red onion variety. I decided that the Rossas with green tops would become subjects in my first attempt to make a braided onion rope. Braiding is another option for curing onions, especially if you don’t have a lot of horizontal space for curing. By braiding the onion tops, you effectively make that little crook-in-the-neck seal that would naturally form when the tops flop over in the field. There are lots of videos online to help you learn to braid onions, and I watched a few before diving in. Basically, you braid the onions like you would braid hair, and you include some twine in the braid to help stabilize everything and to give you a loop to hang the braid from a hook or nail. My Rossa di Milano onion braid is currently hanging from the rafters of my front porch where it will get a little breeze to help the curing process and be protected from the rain.

In seed catalogs, onions are classified as short, intermediate, or long day length onions. You must choose the right type for your spot on the earth. Farms in northerly latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere have long summer days so they should grow long day onions. Farms in southerly latitudes have shorter summer days, so short day onions are most appropriate there. Here in Northern Kentucky, I am almost at 39 degrees latitude, which is the southern edge of the long day onion zone. Most long day onions switch from growing green tops to making big bulbs once there is at least 14 hours of day length, and at my latitude that occurs after May 6 and lasts until August 5. That isn’t as large of a window for bulb formation as Maine or Washington, but it’s still three months, and my onions seem to be small to medium in size, accordingly. The problem with growing short day onions here is that they may bolt (i.e., go to seed) before forming a bulb. Overall, I am happy with the varieties I grew this year, and I will continue to try different long day onion varieties. I wish I had started my onions earlier, tended to them better when they were little baby onions in the greenhouse, and got them transplanted in the field earlier, but even so, I have a lot of onions to show for my efforts this year.

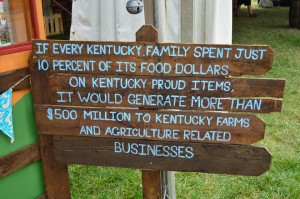

Food Dollars

I have no idea how accurate the sign is, but it got me intrigued to crunch the numbers. [PLEASE LET ME KNOW IF MY MATH DOESN’T ADD UP!!] Assuming that $500 million could be generated if Kentuckians spent 10% of their food dollars on Kentucky Proud products, that means that Kentuckians spend $5 billion each year on food. With roughly 4.4 million people living in the state of Kentucky, that means that every man, woman, and child in Kentucky spends roughly $1,140 on food each year. If each person were to allocate 10% of their food dollars to Kentucky producers, that would come out to $114 per person per year, or $9.50 per person per month. I don’t know about you, but that seems like a totally do-able amount of money to spend each month supporting local farmers, producers, restaurants, and farmers markets. In fact, it seems silly that folks can’t spend more than $10 per month on local food. It certainly will make me look at old Alexander Hamilton a little differently next time he peers up at me from my wallet.

I’m not trying to get super preachy here and say that everyone should make the same food choices as me, but I would challenge you to actively make your own food choices. What is important to you and your family when it comes to food? What kinds of food do you want to eat? Who produces the kind of food you want to eat? Where does that food come from? Your food dollars make a difference for the producers of that food, and it that way, your food dollars can directly support farmers and businesses in your community. But food dollars aren’t all that matters. I once heard someone say that every dollar you spend on food is like a vote, and while I understand the logic behind that idea, it makes me feel a little squirmy. It implies that the people with the most money have the most votes, and people with less money have fewer votes. There are so many things that you can do to support local food that don’t involve “voting” with your dollars. Sure, where you spend your food dollars makes a big difference, but you can also do things like grow some of your own food, whether it’s an expansive garden or just a few containers with basil on your balcony. You can cook more meals at home using local, seasonal ingredients. You can get to know your local food producers, ask them questions about their growing practices, and support them by spreading the word about their businesses. You can volunteer to help out on a farm or a community garden in exchange for food. You can donate fresh, locally grown food to a food pantry. You can support policies in your local government that protect agricultural lands and keep them available to farmers at affordable prices. You can simply just read a book or two about food. All of these activities will make a difference in how you eat, how you think about your food, how you choose to support food producers, and thus have a ripple effect through your food system.

- To look up Kentucky Proud producers, use the Find Kentucky Proud Producers Search Engine

- To find local producers in the Greater Cincinnati area, consult the Central Ohio River Valley (CORV) Local Food Guide. The guide not only lists local producers, but gives information on their growing practices.

Dark Wood Farm FAQ

This past week, while I was out of town for wedding festivities, I caught up with a bunch of old friends. They had lots of questions about my farm, so I thought that this might be a great opportunity to answer those questions for a broader audience. Let’s call it a little Dark Wood Farm FAQ.

How’s the farming going?

It’s going well! It’s a lot of hard work, it keeps me busy, and I’m not getting a lot of sleep at the moment, but I fully expect to make up some of that sleep this winter. I really like being my own boss and being outside everyday. I feel really strong and healthy, and I’m learning so much about growing vegetables through trial and error.

What’s your favorite part of farming so far?

I love cooking food that I grew myself, and I love sharing my vegetables with family and friends. Cooking is a joy for me, and using such fresh, wholesome ingredients makes a huge difference in the quality of my meals. My family and friends are trying all kinds of new veggies out my garden and eating more fresh produce than normal, which really makes me happy. I also love talking to people at the farmers market, sharing recipes, and explaining what to do with all the odd vegetables I grow.

What are you going to do this winter?

Hopefully I will get some much-needed rest and do some traveling, but I’ll probably have to pick up a holiday job to make a little extra money. I will also have lots to keep me busy: planning next year’s crops, ordering seeds, cleaning and fixing equipment, and building new gadgets and infrastructure to make farm work easier!

Are you making any money?

Talking about money is awkward, especially when you’re starting a new business, but I think it’s important to talk about it so that consumers are aware of how hard farmers work and how little they get paid. I’m sure we all wish food was free, but we live in a world where most people don’t grow their own food, so the people that do grow food need to be compensated for the hard work they do to keep everyone fed with nutritious, safe, and delicious food. Yes, I am making money at the farmers markets, but I don’t know yet if I’ll recover all my expenses this year. At the beginning of the year, I bought a bunch of equipment and supplies to get me started, plus I always have my monthly rent and utility bills for the farm. It would be amazing if I could make everything back this year and have a little left over to pay myself, but most new businesses don’t make money in their first year because of all the upfront equipment costs. I’ll be able to answer this question a little better at the end of the year. Suffice it to say, I have a lot of vegetables to sell and I am selling them, but I don’t expect to get rich this year or any other year, for that matter. Farming is not a lucrative business, but most farmers don’t farm because they’re hoping to strike it rich.

Do you own the farm?

No, I am leasing the farm this year. The farm belongs to the Mays family, whom I have known for almost 15 years. They are leasing me the land where I grow the vegetables, plus a trailer on the property where I live. I also get to use the tractor and farm implements, and I can harvest from the existing apple trees, blackberry bushes, and strawberry and asparagus patches. I hope to have my own farm one day, but leasing is the best option for me as a first-time farmer. Without the burden of a mortgage, I can figure out if I will be able to farm full time without another income source, if there’s a market for the kinds of vegetables I want to grow, and if I am capable of growing said vegetables in Northern Kentucky’s soils and climate. I learned most of my farming skills in Washington and California, both of which have very different growing conditions than here. It is also extremely helpful to have some existing equipment on hand because it has aided in keeping my first year costs down while I figure out how to run my farming business.

How big is the farm?

The entire farm is roughly 35 acres, most of which is hilly and wooded. The parcel where I grow everything is just under 2 acres. Some of that 2 acres is taken up with grassy headlands, trees along the edges, my greenhouse, and a blackberry patch, so the actual area that I am tilling to grow annual vegetables is 1 acre.

Is your family glad to have you home?

That’s a question best answered by my family, but I am pretty sure they are happy to have me home. I have been away from Kentucky for 10 years, and while it feels like a big change to come home, it also doesn’t. My family and friends have been so wonderfully supportive that it has been pretty easy to pick up where I left off. Sure, I miss my friends in Seattle, but I also miss my friends from New York, and friends that are now scattered all over the country. I wish I could scoop them all up and bring them to my farm so we can all live together, but that’s not very realistic. Luckily, with the support of my friends and family here in Kentucky, I was able to take a little vacation to the West Coast for a wedding in mid-July when the farm was in full swing. I hope I will always be able to take trips like that, and I feel pretty blessed to have friends waiting with open arms wherever I go.

Weeds or Nature’s Support?

This past week on the farm, a major crop of weeds sprouted following two days of heavy rain. Our onions and celery seemed to be engulfed in them overnight. Last Monday, Chris spent half the day clearing out around the onions and on Wednesday, my parents and our friends, Tina and Donna, helped to save the celery. These crops in particular have a hard time out-competing their weed neighbors. They are skinny and tall and don’t send out a lot of horizontal leaves that would shade out their competitors, so they require repeated weeding to ensure they receive sufficient light and water instead of their free-ranging weed neighbors.

Whenever I think of weeds, I think of a story that my friend, Rachel, told me once. She had a plot in a community garden in Nashville and spent a lot of time at her plot pulling weeds. One Sunday, Rachel and her husband were in church and the preacher was talking about weeding as a metaphor for simplifying your life, how plants require water and light and can miss out on those things if they are cluttered by weeds. Suddenly, Rachel’s husband turned to her and said, “Oh, now I get why you spend so much time weeding in the garden!” He thought she was just doing it to keep the garden looking neat and tidy, not realizing how weeding helps your vegetables get all the light and water they require. I’m sure it can look like a tedious job to the non-gardener, but weeding is an essential part of keeping your vegetables happy and healthy.

On the other hand, weeds can actually serve a purpose in your garden. Whenever you have bare soil, weeds are sure to pop up within a few days. Their seeds are ubiquitous in the environment. They float in on the air, are carried into or buried in the garden by animals, and are dropped from parent plants around the edges of your garden. They can live for years in the soil, just waiting for the right conditions to germinate. You don’t have to do anything and they just grow up on their own. That can be nice sometimes. Without the root systems of weeds, bare soil will wash away in a strong rainstorm. The roots of weeds also harbor bacteria, fungus, protozoa, nematodes, and other microorganisms that help to feed the roots of vegetables in your garden. Weeds can also help keep the soil moist by trapping water between the surface of the soil and their leaves. I have seen super dry bare soil after a hot week without rain, but if you look under a squash plant with weeds around it, the soil is still moist!

One of my farmer mentors, Bob, didn’t like calling them weeds. Instead, he called them “nature’s support” because he saw them as free helpers. He didn’t have to plant them, they just came up on their own, helped keep soil in place, helped keep the soil microorganisms happy, kept the soil moist, and generally added biomass to the garden that would eventually compost down into free soil! Acknowledging that weeds can sometimes grow faster than vegetables and get the edge on sucking up water and sunlight, he would have us do a little “competition control” and that meant cutting back or mowing down “nature’s support” plants so that our vegetables would now be winning in the competition for light and water. Note that we never “weeded” on Bob’s farm. I really like thinking about weeds in this way. So often we vilify “weeds” or “pests” when really they are just trying to live like everything else in the garden, and often they do much better than the things we’re actually trying to grow. Now that I’m a farmer, I realize that you must intervene and give your vegetables the edge if you want to be sure you can eat or have vegetables to sell at the end of the day, but that doesn’t mean that all weeds or bugs need to be eradicated from the garden. They can still live there and contribute, just with some checks and balances from the farmer.

Fridges and Fathers

In honor of Father’s Day, I want to share with you one of the many projects my dad has been working on for the farm – the refrigerated trailer. When I moved onto the farm in January, I knew I was going to need some sort of refrigeration for the vegetables. The summers here get hot and a lot of the vegetables I am growing need to stay cool (down to around 41F) for up to 24 hours before they go to the farmers market. I looked into buying a used large-sized commercial refrigerator, but I don’t have an obvious place to put it where it can be plugged in. The barn would work well because it’s covered, but it doesn’t have power, so that was a no-go. There’s limited covered space around the house, and I was worried about a refrigerator sitting outside and getting wet from the rain and the snow. With that option out, I immediately thought about walk-in coolers. Lots of farms use them, and the farm where I worked outside of Seattle, Local Roots Farm, even had a walk-in cooler that was powered by an air conditioner instead of a compressor. This is an energy-saving option made possible by a little device called a CoolBot that tricks the air conditioner to run at temperatures lower than normally possible. The only problem is that I am renting the farm and don’t plan to be here forever, so it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to install a walk-in.

That’s where the refrigerated trailer comes in. While poking around on Craiglist looking for farm equipment, I came across an ad for a “Veggie Trailer.” It was an insulated 6’x12′ trailer that contained an air conditioning unit inside. The guy who had built it had used it to cool vegetables to take to market, but he was getting out of the vegetable growing business and wanted to sell it. Here was an option that worked for me! The trailer could be pulled up by my house where the air conditioner could be plugged in, it was weather proof and water tight, and could travel with me when I move off this farm onto my own property. So, I bought the trailer and my dad and I hauled it home to the farm, and I started using it to store and cool my vegetables overnight before I’d take them to the market. The only problem was that the air conditioner could only cool the trailer down to about 55F at best, and on warm days, it struggled to get below 70F. That didn’t really help much with my veggie cooling issue, so I had to keep everything inside the trailer iced down to keep them cool enough. But what about the CoolBot?! I knew a CoolBot would help solve my problem, but unfortunately, the air conditioning unit inside my trailer wasn’t compatible with the CoolBot. My dad found a used air conditioner that would work with the CoolBot, and this past week, after he retired for the second time, he spent several days installing the new air conditioner, adding extra insulation to the trailer, and hooking up the CoolBot. The final version of my refrigerated veggie trailer is awesome, and it’s now sitting out in the shade under a big sycamore tree next to my house waiting to be put to use. We had to work out some electrical issues over the last few days, but everything is up and running and the CoolBot-powered air conditioner is cooling the inside of the trailer from ambient temperature down to 40 degrees in less than 15 minutes, which is amazing!!! I am so excited to put the trailer to use, and can’t thank my handy dad enough for doing all the hard work, especially since he’s retired (again).

Water

Water has been on my mind lately. Mainly because I was worried that my plants weren’t getting enough of it during the final weeks of May. Until a few days ago, the top few inches of soil in the garden were turning dusty dry and the flow of the creeks running alongside my garden had turned from a gush into a trickle. While neighboring farms were busy irrigating their crops, I was busy doing a rain dance because…full disclosure here…I don’t have an irrigation system set up yet. I have a long to-do list for the farm, and setting up irrigation has been on that to-do list for a long time. I kept shuffling it to the bottom of the list because Mother Nature has been providing consistent rain or thundershowers (or snow) since my first seeds and plant babies went out into the field in March. So instead of looking my irrigation (or lack of irrigation) problem in the eye, I focused on other farm projects. Also, I have to admit, irrigation is a topic that makes my head spin, which is probably why I have procrastinated so long.

To irrigate crops, you need a water source and power to deliver the water to the crops. While I’m lucky that I have creeks bordering three sides of my farm, they don’t always hold water consistently throughout the year, and I don’t have an electric source anywhere near my field, so I need to have an alternative power source to pump water from the creeks. Another disclosure – I would rather not have to water at all. If I can get all of my water in the form of rain, it saves me a lot of time and worry. Plus, plants tend to be better at growing deep, water-seeking roots if you don’t water them too much. If the surface of the soil is consistently wet from regular irrigation, the plants will form shallow roots that stay near the surface and easily dry out when they aren’t irrigated. Normally, here in Kentucky, you can bet on warm rains throughout the summer, but we have experienced drought years, and who knows what will happen this summer, so I’m biting the bullet and buying irrigation equipment in case we have an unusually dry summer. Now I’m tackling the confusing-to-me subjects of water pressure, friction loss, filtration, and the puzzle of putting together pumps, fittings, pipes, hoses, valves, and nozzles. On top of all that, I have struggled to find a local irrigation supply store that carries agricultural irrigation products for small scale growers. There sure do seem to be a lot of lawn irrigation contractors and suppliers out there, but not a lot of options for people growing things other than grass. The nearest agricultural irrigation store I could find was in Lexington. I could try and order everything online, but I really wanted to talk to an expert and see how all those little fittings, hoses, and whoozeewhatsits go together before I purchased them. So, earlier this week after some hot days with no rain, I decided to drive to Lexington and talk to the fine people at Kentucky Irrigation. Now I’m the proud owner of some drip tape, a filter, pressure regulator, and various fittings. I still need to purchase a pump and a large diameter hose or pipes to deliver water from the pump up the field, but all of that can wait a little longer because my rain dance paid off – on Wednesday, we received an inch of rain. As luck might have it, most of it fell during the few hours we have to harvest vegetables for our Wednesday farmers market, but I’m not complaining. The plants are thriving now in moist soil and I get to procrastinate my irrigation problem for a little longer.

New Arrivals

The big news on the farm this week is that help (and company!) has arrived. My friend, Chris “Vyper” Pyper and his feline companion, Smudge, will be living and working with me here on the farm through the growing season. And, yes, Smudge has to work too – she’s on bug killing duty in the house. Chris and I met when we volunteered for the same AmeriCorps program in 2010. We both led trail crews in the Pacific Northwest – me in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington State and Chris along the Pacific Crest Trail in Northern California and Southern Oregon. We were thrown together often for trainings and special events, and when we realized we would both be moving to Seattle after AmeriCorps, we promised to stay in touch. It wasn’t long after we both moved to Seattle that we realized it would be fun and cost-effective to be roommates, especially because we shared a love for cooking local, sustainably grown food. Chris and I lived in a few places around Seattle, but we always had a garden, whether in the ground or in containers on our balcony. We even converted a little shed into a chicken coop and kept four laying hens in our backyard in urban Seattle. Aside from his full time job at the Mountaineers, Chris worked for Nash’s Organics at two of Seattle’s largest farmers markets, while I started exploring the ins and outs of farming as a volunteer at the University of Washington Farm and then as an employee at Local Roots Farm.

When I left Seattle to move home and start my farm this year, it was bittersweet. While I was excited to return home to my family and friends in Kentucky, I was very sad to leave my wonderful friends in Seattle, especially Chris who had been an amazing roommate and friend (and Smudge wasn’t so bad either). Now that Chris has decided to come spend his summer and early fall at Dark Wood Farm, I am overjoyed. We have already accomplished so much during his first week here, and we are cooking some pretty amazing meals from all that the farm has to offer, with a little help from our fellow market vendors too. So far, Chris is adapting to the humid heat of Kentucky (he grew up in the dry heat of Utah), and we both got called “city people” while hauling water from the local well today, but we are both enjoying the sunsets, listening to the birds while we work, and sharing the bounty of the farm with family, friends, and market-goers alike.

Welcome to our website!

Hi! You’ve found our very first blog post, and it’s about our new website. This is a work in progress, so check back frequently as things will be a-changin’. Mega-thanks go to my pal, Eric, for helping get this site up and running, and Morgan for keeping us fueled with pasta and nitrate-free chicken sausage while we work.