The Bengals Effect

On Being an Eater

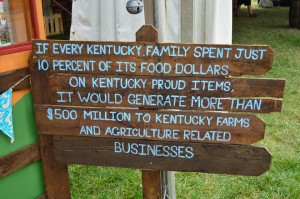

Food Dollars

I have no idea how accurate the sign is, but it got me intrigued to crunch the numbers. [PLEASE LET ME KNOW IF MY MATH DOESN’T ADD UP!!] Assuming that $500 million could be generated if Kentuckians spent 10% of their food dollars on Kentucky Proud products, that means that Kentuckians spend $5 billion each year on food. With roughly 4.4 million people living in the state of Kentucky, that means that every man, woman, and child in Kentucky spends roughly $1,140 on food each year. If each person were to allocate 10% of their food dollars to Kentucky producers, that would come out to $114 per person per year, or $9.50 per person per month. I don’t know about you, but that seems like a totally do-able amount of money to spend each month supporting local farmers, producers, restaurants, and farmers markets. In fact, it seems silly that folks can’t spend more than $10 per month on local food. It certainly will make me look at old Alexander Hamilton a little differently next time he peers up at me from my wallet.

I’m not trying to get super preachy here and say that everyone should make the same food choices as me, but I would challenge you to actively make your own food choices. What is important to you and your family when it comes to food? What kinds of food do you want to eat? Who produces the kind of food you want to eat? Where does that food come from? Your food dollars make a difference for the producers of that food, and it that way, your food dollars can directly support farmers and businesses in your community. But food dollars aren’t all that matters. I once heard someone say that every dollar you spend on food is like a vote, and while I understand the logic behind that idea, it makes me feel a little squirmy. It implies that the people with the most money have the most votes, and people with less money have fewer votes. There are so many things that you can do to support local food that don’t involve “voting” with your dollars. Sure, where you spend your food dollars makes a big difference, but you can also do things like grow some of your own food, whether it’s an expansive garden or just a few containers with basil on your balcony. You can cook more meals at home using local, seasonal ingredients. You can get to know your local food producers, ask them questions about their growing practices, and support them by spreading the word about their businesses. You can volunteer to help out on a farm or a community garden in exchange for food. You can donate fresh, locally grown food to a food pantry. You can support policies in your local government that protect agricultural lands and keep them available to farmers at affordable prices. You can simply just read a book or two about food. All of these activities will make a difference in how you eat, how you think about your food, how you choose to support food producers, and thus have a ripple effect through your food system.

- To look up Kentucky Proud producers, use the Find Kentucky Proud Producers Search Engine

- To find local producers in the Greater Cincinnati area, consult the Central Ohio River Valley (CORV) Local Food Guide. The guide not only lists local producers, but gives information on their growing practices.

Tasty Tomatoes

My friend, Morgan, had Chris and me over for dinner last night, and she put in a special request that we bring over some heirloom tomatoes. I was happy to oblige; we have plenty of them at the moment, and we are excited to share them with our friends and family. I brought over several varieties and we taste tested at least three, all of which where juicy, dense, and sweet. Morg asked, “Why do heirlooms taste so much better?” and I thought y’all might have the same question, so here’s my answer in several parts:

Let’s start by discussing just what the heck makes a tomato (or any other vegetable, for that matter), an “heirloom.” Do any of you have an old piece of jewelry or antique passed down through your family? When I turned 15, my aunt, Jennifer, gave me a little gold ring that she had received on her 15th birthday from my great grandmother, Mutzi. In turn, Mutzi had received the ring on her 15th birthday from her father. That’s an heirloom. Something that has been passed down over the years through the generations of a family. Now, let’s shift the gears and talk about heirloom vegetables. In the days before seed catalogs, folks would save seeds from the myriad vegetables they were growing for fresh eating and preserving, and plant those saved seeds in subsequent year. In fact, a family could save the seed from their best, most flavorful, most vigorous and healthy plants, and by doing that every year, improve their vegetables’ taste, texture, and production at that specific location. Let’s fast forward to what agriculture looks like today. We now live in a world where vegetable production has converted from diverse backyard gardens to large-scale monocultures, meaning vast acreages of one crop, often picked by a machine instead of by a human hand. We also live in a world where we seldom walk out the back door, pick our vegetables, and eat them immediately. Instead, we go to the grocery store and buy vegetables that were picked at an unknown date, packed, and shipped some unknown number of miles away. For a vegetable to be “successful” in today’s agricultural world, it must maximize production per acre, be easy to pick by a machine, be easily washed and packed, resist bruising during shipping, sit stably on a shelf for an untold amount of time, be uniform in color, shape, and size so it displays nicely, and last for weeks in your refrigerator’s vegetable drawer. So, instead of seed that has been saved by families for flavor, ripeness, and vigor in a specific location, we now eat vegetables from seeds that were saved for uniformity, hardness (for shipping purposes), and shelf stability. Note that I did not include “flavor” in that list. To achieve these modern goals, people have done crazy things to seeds, including inserting genetic material from other life forms into the DNA of vegetables, making them genetically modified organisms, or GMOs.

Most vegetables develop flavor as they approach ripeness. This is especially the case with tomatoes. Ever eat one of those hard, white-in-the-center, tomatoes from the grocery store in January? They have absolutely no flavor because they were picked under-ripe to keep them hard for shipping. A tomato that is allowed to ripen on the vine has time to develop sugars, which cause the tomato to be soft to the touch, juicy when cut, fragrant, and sweet. The sugars also cause the tomato to rapidly decay and soften if you don’t eat them shortly after they are picked. A soft, sugary tomato does NOT travel well, and it certainly doesn’t travel well over thousands of miles. Really, the only way to get your hands on one of these babies is to grow them and pick them yourself or to buy them from someone growing them nearby. This is where your friendly, small-scale farmer comes into play. Small-scale farmers can pick tomatoes by hand, noting which are at their peak of ripeness, handle them gently, and deliver them to a market or to your doorstep in a short amount of time. Small-scale farmers can peddle even the ugliest of tomatoes, including cracked and crazy-looking tomatoes (as heirlooms often are), because they can talk with their customer one-on-one, describe the flavor, describe their growing practices, let you smell, touch, and even taste test the vegetables. Farmers that grow for wholesale simply can’t do this.

While I do have my great grandma’s heirloom ring, I don’t have any heirloom seeds that were passed down in my family. Luckily, there are a lot of small-scale growers out there, dutifully saving seeds from old heirloom varieties and sharing them with other farmers. This year, I ordered most of my seeds from Fedco, a seed co-op based in Maine, and Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, which is a network of growers that specialize in varieties that grow well in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern US. Through the hard work of these growers, many heirloom varieties live on and are available for growers like me – new farmers just getting started and in need of delicious locally-adapted varieties to grow for their friends, family, and neighbors.

Dark Wood Farm FAQ

This past week, while I was out of town for wedding festivities, I caught up with a bunch of old friends. They had lots of questions about my farm, so I thought that this might be a great opportunity to answer those questions for a broader audience. Let’s call it a little Dark Wood Farm FAQ.

How’s the farming going?

It’s going well! It’s a lot of hard work, it keeps me busy, and I’m not getting a lot of sleep at the moment, but I fully expect to make up some of that sleep this winter. I really like being my own boss and being outside everyday. I feel really strong and healthy, and I’m learning so much about growing vegetables through trial and error.

What’s your favorite part of farming so far?

I love cooking food that I grew myself, and I love sharing my vegetables with family and friends. Cooking is a joy for me, and using such fresh, wholesome ingredients makes a huge difference in the quality of my meals. My family and friends are trying all kinds of new veggies out my garden and eating more fresh produce than normal, which really makes me happy. I also love talking to people at the farmers market, sharing recipes, and explaining what to do with all the odd vegetables I grow.

What are you going to do this winter?

Hopefully I will get some much-needed rest and do some traveling, but I’ll probably have to pick up a holiday job to make a little extra money. I will also have lots to keep me busy: planning next year’s crops, ordering seeds, cleaning and fixing equipment, and building new gadgets and infrastructure to make farm work easier!

Are you making any money?

Talking about money is awkward, especially when you’re starting a new business, but I think it’s important to talk about it so that consumers are aware of how hard farmers work and how little they get paid. I’m sure we all wish food was free, but we live in a world where most people don’t grow their own food, so the people that do grow food need to be compensated for the hard work they do to keep everyone fed with nutritious, safe, and delicious food. Yes, I am making money at the farmers markets, but I don’t know yet if I’ll recover all my expenses this year. At the beginning of the year, I bought a bunch of equipment and supplies to get me started, plus I always have my monthly rent and utility bills for the farm. It would be amazing if I could make everything back this year and have a little left over to pay myself, but most new businesses don’t make money in their first year because of all the upfront equipment costs. I’ll be able to answer this question a little better at the end of the year. Suffice it to say, I have a lot of vegetables to sell and I am selling them, but I don’t expect to get rich this year or any other year, for that matter. Farming is not a lucrative business, but most farmers don’t farm because they’re hoping to strike it rich.

Do you own the farm?

No, I am leasing the farm this year. The farm belongs to the Mays family, whom I have known for almost 15 years. They are leasing me the land where I grow the vegetables, plus a trailer on the property where I live. I also get to use the tractor and farm implements, and I can harvest from the existing apple trees, blackberry bushes, and strawberry and asparagus patches. I hope to have my own farm one day, but leasing is the best option for me as a first-time farmer. Without the burden of a mortgage, I can figure out if I will be able to farm full time without another income source, if there’s a market for the kinds of vegetables I want to grow, and if I am capable of growing said vegetables in Northern Kentucky’s soils and climate. I learned most of my farming skills in Washington and California, both of which have very different growing conditions than here. It is also extremely helpful to have some existing equipment on hand because it has aided in keeping my first year costs down while I figure out how to run my farming business.

How big is the farm?

The entire farm is roughly 35 acres, most of which is hilly and wooded. The parcel where I grow everything is just under 2 acres. Some of that 2 acres is taken up with grassy headlands, trees along the edges, my greenhouse, and a blackberry patch, so the actual area that I am tilling to grow annual vegetables is 1 acre.

Is your family glad to have you home?

That’s a question best answered by my family, but I am pretty sure they are happy to have me home. I have been away from Kentucky for 10 years, and while it feels like a big change to come home, it also doesn’t. My family and friends have been so wonderfully supportive that it has been pretty easy to pick up where I left off. Sure, I miss my friends in Seattle, but I also miss my friends from New York, and friends that are now scattered all over the country. I wish I could scoop them all up and bring them to my farm so we can all live together, but that’s not very realistic. Luckily, with the support of my friends and family here in Kentucky, I was able to take a little vacation to the West Coast for a wedding in mid-July when the farm was in full swing. I hope I will always be able to take trips like that, and I feel pretty blessed to have friends waiting with open arms wherever I go.

Wasps and Washing

Chris and I do most of our vegetable picking in the morning when the plants are cool(er) and moist. Once the veggies heat up, they respire faster, which leads to wilting. We want the vegetables we sell at market to look nice and perky and to last longer in your refrigerator, so it’s imperative to get them out of the field in the morning when their respiration rate is lower. Once they are picked, almost all the veggies get sprayed off by the hose on a wire mesh spray table or dunked in water to remove dirt from the field. My dad helped me construct an elevated stand that holds a bath tub that I can fill with water for cleaning the vegetables. The dirty water is easily drained out of the bottom of the tub, then it gets cleaned and sanitized before the next round of vegetables comes in to be cleaned. Once the vegetables are rinsed, they are organized in plastic totes and placed into our awesome veggie cooler trailer and kept at 39-40 degrees F until they go to market. I have several bottles of water that I freeze before the market, then place inside the totes once we open them at the market. That helps hold the vegetables at a cool temperature inside the totes for the 3-4 hours we’re at the market. Keeping the veggies fresh and clean looking is definitely time and energy consuming, but I think the end result is worth it – several customers have told me how long their Dark Wood Farm vegetables last. Even though Chris, my mom, and I spend a lot of time cleaning the vegetables, I always suggest that you wash again at home. We don’t use any sprays or dangerous chemicals on your veggies, so you don’t need to worry about that. However, an extra rinse with cool water will help remove extra dirt that didn’t come off in the first rinse and help alleviate any wilting that happens during the time between buying the vegetables and getting them in your fridge.

New Arrivals

The big news on the farm this week is that help (and company!) has arrived. My friend, Chris “Vyper” Pyper and his feline companion, Smudge, will be living and working with me here on the farm through the growing season. And, yes, Smudge has to work too – she’s on bug killing duty in the house. Chris and I met when we volunteered for the same AmeriCorps program in 2010. We both led trail crews in the Pacific Northwest – me in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington State and Chris along the Pacific Crest Trail in Northern California and Southern Oregon. We were thrown together often for trainings and special events, and when we realized we would both be moving to Seattle after AmeriCorps, we promised to stay in touch. It wasn’t long after we both moved to Seattle that we realized it would be fun and cost-effective to be roommates, especially because we shared a love for cooking local, sustainably grown food. Chris and I lived in a few places around Seattle, but we always had a garden, whether in the ground or in containers on our balcony. We even converted a little shed into a chicken coop and kept four laying hens in our backyard in urban Seattle. Aside from his full time job at the Mountaineers, Chris worked for Nash’s Organics at two of Seattle’s largest farmers markets, while I started exploring the ins and outs of farming as a volunteer at the University of Washington Farm and then as an employee at Local Roots Farm.

When I left Seattle to move home and start my farm this year, it was bittersweet. While I was excited to return home to my family and friends in Kentucky, I was very sad to leave my wonderful friends in Seattle, especially Chris who had been an amazing roommate and friend (and Smudge wasn’t so bad either). Now that Chris has decided to come spend his summer and early fall at Dark Wood Farm, I am overjoyed. We have already accomplished so much during his first week here, and we are cooking some pretty amazing meals from all that the farm has to offer, with a little help from our fellow market vendors too. So far, Chris is adapting to the humid heat of Kentucky (he grew up in the dry heat of Utah), and we both got called “city people” while hauling water from the local well today, but we are both enjoying the sunsets, listening to the birds while we work, and sharing the bounty of the farm with family, friends, and market-goers alike.

Spring Greens

This weekend marks a momentous occasion for me and the farm – my first trip to the farmers market! Four busy months have passed since I moved onto my little piece of leased land down in Belleview Bottoms, and now it’s time for the vegetables of Dark Wood Farm to make their grand debut and start filling the bellies of folks around Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati. On Sunday, May 4 from 10AM-2PM, I’ll be bringing lots of spring greens to the farmers market at Findlay Market. Spring greens are a great source of vitamins, minerals, and fiber, which improve digestion and help your body detox after a long winter of heavy, fatty foods. As a bonus, most spring greens will enliven your taste buds with a spicy kick, bold nutty flavor, or bitter bite.

Most of the greens I’m bringing to market this week are in the mustard plant family, including arugula, french breakfast radishes, and Asian salad greens including mizuna and tatsoi. They went into the ground as seeds on March 24 and have grown happily through the cold, wind, rain, and even heat over the past 6 weeks. Their only nemesis during the spring months is a small, black, jumping insect called the flea beetle. Flea beetles emerge around the same time that the redbud trees bloom here in Kentucky, and when they start looking for food, they LOVE the spicy flavor of plants in the mustard family. Left unprotected from the flea beetle, spring mustards would look like they were blasted by a shotgun, with tiny holes all over the leaves. Some farmers prevent flea beetle damage by applying weekly doses of insecticides, but I don’t want to eat raw greens covered with chemicals, so I use fabric row covers to cover the vegetables that are most susceptible to flea beetle damage. Even so, some flea beetles find their way under the fabric and leave their trademark holes on my spring greens.

Since I cut spring greens by hand, I can check for flea beetle damage as I harvest. Really holey leaves get tossed on the ground become compost and feed the soil, but I do keep some leaves that have minimal damage from the flea beetle. The holes do nothing to affect the taste and quality of the vegetables, so if you find an arugula or radish leaf with a hole or two, don’t worry – in fact, rest assured that your veggies are free from chemicals and safe to eat.

CORV Local Food Guide

If you live in the Northern Kentucky/Greater Cincinnati area and love local food, then you should pick up a copy of the 2014 Central Ohio River Valley (CORV) Local Food Guide. Inside you’ll find listings for local farms, farmers markets, wineries, restaurants, and community supported agriculture (CSA) programs. You can download the guide here.